The

Career of the Confederate Ram Albemarle

II. An Attempt to Run Down an

Iron-Clad With a Wooden Ship

By Edgar Holden, M.D., U. S. N.

(From The Century, Volume 36,

Issue 3, July 1888, pp427-432.)

|

|

|

|

|

The United States steamer Sassacus was one of several wooden side-wheel ships, known as “double-enders,” built for speed, light draught, and ease of maneuver in battle, as they could go ahead or hack with equal facility. She carried four 9-inch Dahlgren guns and two 100-pounder Parrott rifles. On the 5th of May, 1864, this ship, while engaged, together with the Mattabesett, Wyalusing, and several smaller vessels, with the Confederate iron-clad Albemarle in Albemarle Sound, was, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander F. A. Roe, and with all the speed attainable, driven down upon the ram, striking full and square at the junction of its armored roof and deck. It was the first attempt of the kind and deserves a place in history. This sketch is an endeavor to recall only the part taken in the engagement by the Sassacus in her attempt to run down the ram. One can obtain a fair idea of the

magnitude of such an undertaking by remembering that on a ship in battle

you are on a floating target, through which the enemy’s shell may

bring not only the carnage of explosion but an equally unpleasant

visitor — the sea. To hurl this egg-shell target against a rock would

be dangerous, but to hurl it against an iron-clad bristling with guns,

or to plant it upon the muzzles of 100-pounder Brooke or Parrott rifles,

with all the chances of a sheering off of the iron-clad, and a

subsequent ramming process about which no two opinions ever existed, is

more than dangerous. |

Lt-Commander

F. A. Roe |

On the 17th of April, 1864, Plymouth, N. C., was attacked by the Confederates by land and river. On the 20th it was captured, the ram Albemarle having sunk the Southfield and driven off the other Union vessels.

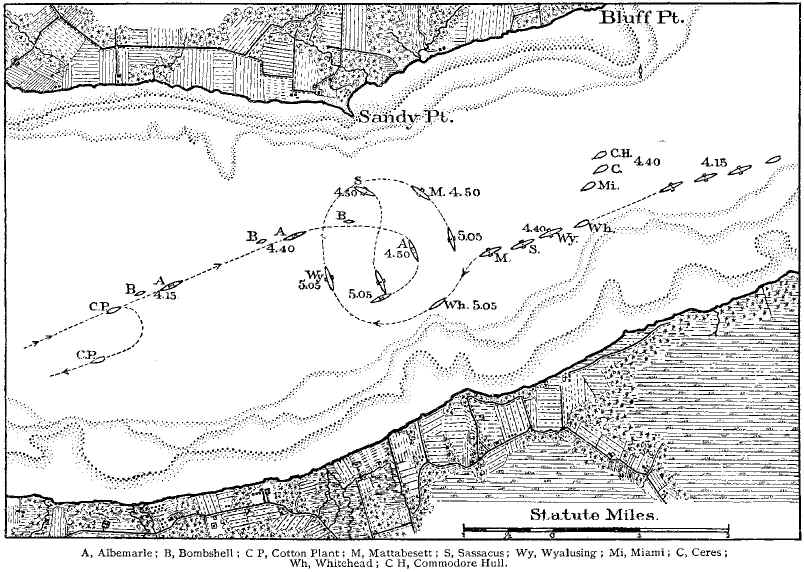

On the 5th of May the Albemarle, with the captured steamer Bombshell and the steamer Cotton Plant, laden with troops, came down the river. The double-enders Mattabesett, Sassacus, Wyalusing, and Miami, together with the smaller vessels, Whitehead, Ceres, and Commodore Hull steamed up to give battle.

The Union plan of attack was for the large vessels to pass as close as possible to the ram without endangering their wheels, deliver their fire, and then round to for a second discharge. The smaller vessels were to take care of thirty armed launches, which were expected to accompany the iron-clad. The Miami carried a torpedo to be exploded under the enemy, and a strong net or seine to foul her propeller.

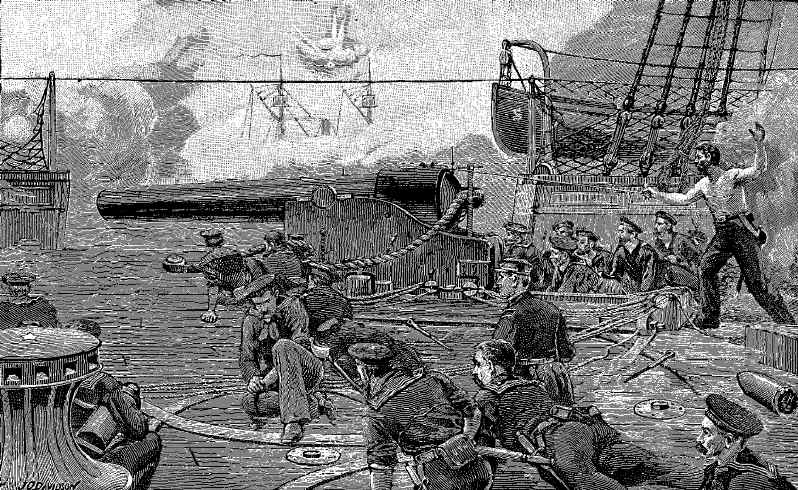

All eyes were fixed on this second Merrimac as, like a floating fortress, she came down the bay. A puff of smoke from her bow port opened the ball, followed quickly by another, the shells aimed skillfully at the pivot-rifle of the leading ship, Mattabesett, cutting away rail and spars, and wounding six men at the gun. The enemy then headed straight for her, in imitation of the Merrimac, but by a skillful management of the helm the Mattabesett rounded her bow, (1) closely followed by our own ship, the Sassacus, which at close quarters gave her a broadside of solid 9-inch shot. The guns might as well have fired blank cartridges, for the shot skimmed off into the air, and even the 100-pound solid shot from the pivot-rifle glanced from the sloping roof into space with no apparent effect. The feeling of helplessness that comes from the failure of heavy guns to make any mark on an advancing foe can never be described. One is like a man with a bodkin before a Gorgon or a Dragon, a man with straws before the wheels of Juggernaut.

To add to the feeling in this instance, the rapid firing from the different ships, the clouds of smoke, the changes of position to avoid being run down, the watchfulness to get a shot into the ports of the ram, as they quickly opened to deliver their well-directed fire, kept alive the constant danger of our ships firing into or entangling each other. The crash of bulwarks and rending of exploding shells which were fired by the ram, but which it was utterly useless to fire from our own guns, gave confused sensations of a general and promiscuous mode, rather than a well-ordered attack; nevertheless the plan designed was being carried out, hopeless as it seemed. As our own ship delivered her broadside, and fired the pivot-rifle with great rapidity at roof, and port, and hull, and smoke-stack, trying to find a weak spot, the ram headed for us and narrowly passed our stern. She was foiled in this attempt, as we were under full headway, and swiftly rounding her with a hard-port helm, we delivered a broadside at her consort, the Bombshell; each shot hulling her. We now headed for the latter ship, going within hail.

Thus far in the action our pivot-rifle astern had had but small chance to fire, and the captain of the gun, a broad-shouldered, brawny fellow, was now wrought up to a pitch of desperation at holding his giant gun in leash, and as we came up to the Bombshell he mounted the rail, and, naked to the waist, he brandished a huge boarding-pistol and shouted, “Haul down your flag and surrender, or we’ll blow you out of the water!” The flag came down, and the Bombshell was ordered to drop out of action and anchor, which she did. Of this surrender I shall have more to say farther on.

|

Acting-Master

Charles Boutelle

|

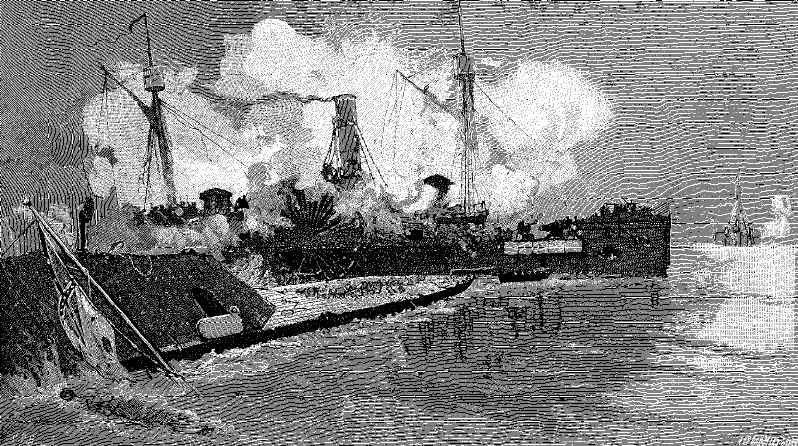

|

Both ships were under headway, and as the ram advanced, our shattered bows clinging to the iron casemate were twisted round, and a second shot from a Brooke gun almost touching our side crashed through, followed immediately by a cloud of steam and boiling water that filled the forward decks as our overcharged boilers, pierced by the shot, emptied their contents with a shrill scream that drowned for an instant the roar of the guns. The shouts of command and the cries of scalded, wounded, and blinded men mingled with the rattle of small-arms that told of a hand-to-hand conflict above. The ship surged heavily to port as the great weight of water in the boilers was expended, and over the cry, “The ship is sinking!” came the shout, “All hands repel boarders on starboard bow!”

The men below, wild with the boiling steam, sprang to the ladder with pistol and cutlass, and gained the bulwarks; but men in the rigging with muskets and hand grenades, and the well-directed fire from the crews of the guns, soon baffled the attempt of the Confederates to gain our decks. To send our crew on the grated top of the iron-clad would have been madness.

The horrid tumult, always characteristic of battle, was intensified by the cries of agony from the scalded and frantic men. Wounds may rend, and blood flow, and grim heroism keep the teeth set firm in silence; but to be boiled alive — to have the flesh drop from the face and hands, to strip off in sodden mass from the body as the clothing is torn away in savage eagerness for relief, will bring screams from the stoutest lips. In the midst of all this, when every man had left the engine room, our chief engineer, Mr. Hobby, although badly scalded, stood with heroism at his post; nor did he leave it till after the action, when he was brought up, blinded and helpless, to the deck. I had often before been in battle; had stepped over the decks of a steamer in the Merrimac fight when a shell had exploded, covering the deck with fragments of human bodies, literally tearing to pieces the men on the small vessel as she lay alongside the Minnesota, but never before had I experienced such a sickening sensation of horror as on this occasion, when the bow of the Sassacus lay for thirteen minutes on the roof of the Albemarle. An officer of the Wyalusing says that when the dense smoke and steam enveloped us they thought we had sunk, till the flash of our guns burst through the clouds, followed by flash after flash in quick succession as our men recovered from the shock of the explosion.

"All hands lie down!"

Albemarle rams Sassacus

In Commander Febiger’s report the time of our contact was said to be “some few minutes.” To us, at least, there seemed time enough for the other ships to close in on the ram and sink her, or sink beside her, and it was thirteen minutes as timed by an officer, who told me; hut the other ships were silent, and with stopped engines looked on as the clouds closed over us in the grim and final struggle.

Captain French of the Miami, who had bravely fought his ship at close quarters, and often at the ship’s length, vainly tried to get bows on, to come to our assistance and use his torpedo; but his ship steered badly, and he was unable to reach us before we dropped away. In the mean time the Wyalusing signaled that she was sinking—a mistake, but one that affected materially the outcome of the battle. We struck exactly at the spot for which we had aimed; and, contrary to the diagram given in the naval report for that year, the headway of both ships twisted our bows, and brought us broadside to broadside — our bows at the enemy’s stern and our starboard paddle—wheel on the forward starboard angle of his casemate. Against the report mentioned, I not only place my own observation, but I have in my possession the written statement of the navigator, Boutelle, now a member of Congress from Maine.

At length we drifted off the ram, and our pivot-gun, which had been fired incessantly by Ensign Mayer, almost muzzle to muzzle with the enemy’s guns, was kept at work till we were out of range.

The official report says that the other ships were then got in line and fired at the enemy, also attempting to lay the seine to foul his propeller — a task that proved, alas, as impracticable as that of injuring him by the fire of the guns. While we were alongside, and had drifted broadside to broadside, our 9-inch Dahlgren guns had been depressed till the shot would strike at right angles, and the solid iron would bound from the roof into the air like marbles, and with as little impression. Fragments even of our 100-pound rifle-shots. at close range, came back on our own decks.

At dusk the ram steamed into the Roanoke River. Had assistance been rendered during the long thirteen minutes that the Sassacus lay over the ports of the Albemarle, the heroism of Commander Roe would have electrified the public and made his name, as it should be, imperishable in the annals of naval warfare. There was no lack of courage on the other ships, and the previous loss of the Southfield, the signal from the Wyalusing that she was sinking, the apparent loss of our ship, and the loss of the sounds of North Carolina if more were disabled, dictated the prudent course they adopted.

Of the official reports, which gave no prominence to the achievement of Commander Roe and have placed an erroneous record on the page of history, I speak only with regret.(2) He was asked to correct his report as to the speed of our ship. He had said we were going at a speed of ten knots, and the naval report says, “He was not disposed to make the original correction.” I should think not! — when the speed could only be estimated by his own officers, and the navigator says clearly in his report eleven knots. We had perhaps the swiftest ship in the navy. We had backed slowly to increase the distance; with furious fires and a gagged engine working at the full stroke of the pistons,— a run of over four hundred yards, with eager and excited men counting the revolutions of our paddles; who should give the more correct statement?

The ship first in the line claimed the capture of the Bombshell. The captain of that vessel, afterward a prisoner on our ship. said he surrendered to the second ship in the line, viz., the Sassacus; that the flag was not hauled down till he was ordered to do so by Commander Roe; and that no surrender had been intended till the order came from the second vessel in the line.

Another part of the official report states that the bows of the double-enders were all frail, and had they been armed would have been insufficient to have sunk the ram. If this were so, then was the heroism of the trial the greater. Our bow, however, was shod with a bronze beak, weighing fully three tons, well secured to prow and keel; and this was twisted and almost entirely torn away in the collision.

But what avails it to a soldier to dash over the parapet and seize the colors of the enemy if his regiment halts outside the chevaux de frise? I’ve have always felt that a similar blow on the other side, or a close environment of the heavy guns of the other ships, would have captured or sunk the ram. As it was, she retired, never again to emerge for battle from the Roanoke River, and the object of her coming on the day of our engagement, viz., to aid the Confederates in an attack on New Berne, was defeated; but her ultimate destruction was reserved for the gallant Lieutenant Cushing, of glorious memory.

__________

[1]

If

the Mattabesett rounded the bow of the Albemarle, the latter most have been

heading up the sound at the time; in other words, she must have turned previous

to the advance of the Union fleet. Upon this point the reports of the captains

of the double-enders give conflicting testimony. Commander Febiger represents

the ram as retreating towards the Roanoke, while Lieutenant-Commander Roe

describes her as in such a position that she would necessarily have been heading

towards the advancing squadron. The conflict of opinion was doubtless due to the

similarity in the two ends of the ram.— EDITOR.

[2] NOTE. The Navy Department was not satisfied with the first official reports, and new and special reports were called for. As a result of investigation, promotions of many of the officers were made.— EDITOR.